Input Needed On Using AI To Create Lay Summaries Of Trial Results

The role AI can play in creating lay summaries of clinical trial results.

Kimberly Dorris, Graves’ Disease Patient Advocate

After her Graves' Disease diagnosis, Kimberly Dorris pursued patient education and advocacy full time.

Noa Greenwood, Canavan Disease Clinical Trial Participant

The Greenwood family shares their experience navigating their daughter's rare disease diagnosis and the difference clinical research has made for Noa.

Michael Herman, Multiple Myeloma Clinical Trial Participant & Advocate

Mike's passion for patient advocacy was sparked after receiving a shocking diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Latest CISCRP Patient Survey Reveals Diversity Gaps, Yields 5 Tips For Improvement

More effort is needed to understand the views of underserved groups, such as ethnic and racial minorities, toward clinical research

Round-Up: Highlighting Recent Health Literacy Educational Materials

Round-Up: Highlighting Recent Health Literacy Educational Materials

Community Trust: The Foundation for Fostering Diversity in Clinical Trials

Racial and ethnic minority populations have historically been underrepresented in clinical trials.

A “Day in the Life” of a Medical Writer at CISCRP

It is Monday morning at the CISCRP office, and I open my computer a few minutes

Plain Language Protocol Synopsis 101

Should Sponsors Add a Plain Language Protocol Synopsis to Future Clinical Trial Applications?

CISCRP’s Finding Treatments Together Brochure for LGBTQ+ Communities

Our Approach to Codeveloping an Educational Resource for the LGBTQ+ Community

Brittany Foster, Pulmonary Hypertension Patient Advocate

Britt shares her experience navigating the healthcare system and living with complex medical diagnoses.

Katie Hill, Appendix Cancer Clinical Trial Participant

Katie, an appendix cancer clinical trial participant, shares her experience and advice.

The Importance of Transgender and Non-Binary Inclusion in Clinical Research

At CISCRP, we value the importance of engaging and informing the groups that are underrepresented in clinical trials.

Scott Germain, PTSD Patient Advocate

Scott shares his experience getting treatment for PTSD and a TBI and his passion for bringing awareness to these issues in the veteran community.

Ella Balasa, Cystic Fibrosis Advocate & Patient Engagement Consultant

Ella shares her own experience living with Cystic Fibrosis, clinical research, and her journey to becoming a full-time patient advocate.

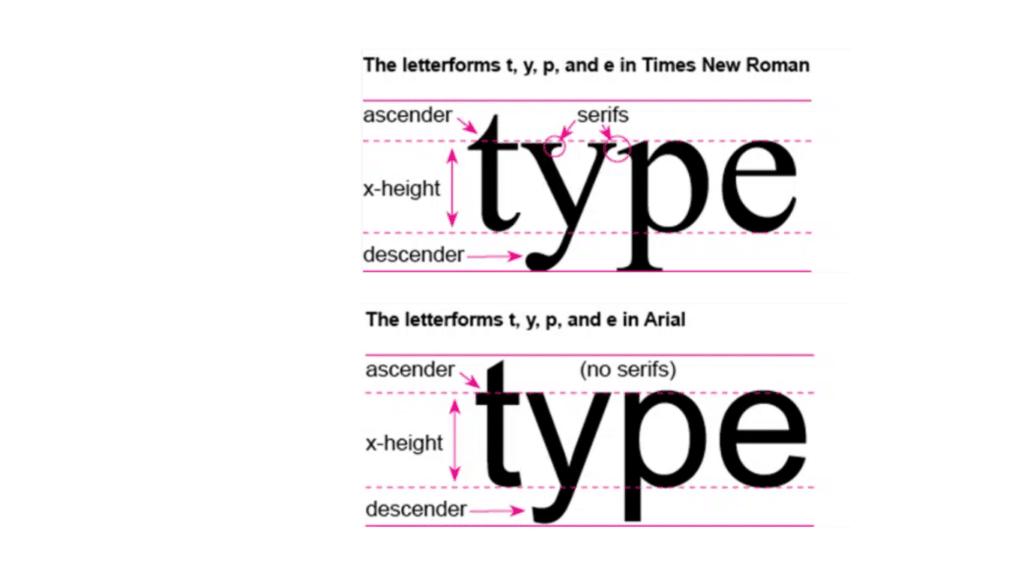

Best Practices in Design for Clinical Trial Communications: The Mysterious Art of Typography

CISCRP produces a wide range of patient-friendly materials, such as informed consent forms, brochures, and trial summaries.

Why Diversity in Clinical Trials Matters – May 2023 Patient Diversity Campaign

Article from our 2023 May Patient Diversity Campaign

Dee Burlile, Scleroderma Clinical Trial Participant & Patient Advocate

Dee shares her experience as a scleroderma patient advocate and clinical trial participant.

The Importance of Patient Engagement and its Role in Clinical Trials

The Importance of Patient Engagement and its Role in Clinical Trials

Tom Smith, Rare Disease Advocate & Patient Engagement Consultant

Tom shares how his own experience living with cystic fibrosis has helped share a career focused on patient engagement and advocacy.

Behind the Scenes of Health Literacy at the Movies

Learn about the infographic that contains an exercise to help readers brush up on their health literacy knowledge.

How CISCRP Made Tools for Informed Decision Making

How CISCRP communicates clinical research information to the public

Improving Accessibility in Clinical Trials

How to improve accessibility in clinical research

Katie Doble & Her Caregivers: Facing Ocular Melanoma

Katie shares her story as an ocular melanoma survivor and the role clinical research played in her treatment.

Allison Kuban, Pancreatic Cancer Clinical Trial Participant

Allison shares her experience living with pancreatic cancer and participating in clinical trial.

Amy Gietzen, Scleroderma Patient Advocate

Amy shares her experience living with scleroderma and participating in clinical research.

Shira Kaplan-Walker, Lupus Patient Advocate

Shira's shares her healthcare journey with lupus and the importance of advocating for yourself as a patient and others in your community.

Voices from Within: Conversations on DCTs & Data Privacy

In Episode Two of Voices from Within: Humanizing Clinical Research Data, Curebase shares a comprehensive overview of how patient data is collected.

Sharan Khela, Crohn’s Disease Patient Advocate

Katie shares her story as an ocular melanoma survivor and the role clinical research played in her treatment.

Alicia Dellario, Ovarian Cancer Clinical Trial Participant

Alicia Dellario shares her story as an ovarian cancer survivor clinical trial participant and how clinical research saved her life.

Medical Heroes Appreci-a-thon: Learn About the Importance of Clinical Research

CISCRP's annual 2023 Appreci-a-thon virtual fitness event

Black Women’s Expo Provides Transformational Experience

CISCRP at the 2022 Black Women's Expo in Atlanta

Improving LGBTQ+ Inclusivity in Ovarian Cancer Care

From an ovarian cancer awareness perspective, there are specific messages for the LGBTQ+ community that need to be communicated.

Kim Zukerberg, Ovarian Cancer Clinical Trial Participant

Kim shares her experience battling ovarian cancer and the impact of clinical trial participation on her health.

Why Participation in Clinical Trials Is a Must for Hispanics

Clinical trials need ethnically diverse participants so scientists can develop a greater understanding of how diseases impact different people.

Fred Neubauer, Cholangiocarcinoma Patient Advocate

Fred shares his battle with Cholangiocarcinoma, a rare form of cancer, and his hope to participate in clinical research.

Nia Grant, Type 1 Diabetes Clinical Trial Participant

Nia shares her experience as a passionate advocate and clinical trial participant for Type 1 Diabetes.

DEI Series — Educating Clinical Research Practitioners Through Video

CISCRP partnered with WCG to create a video for researchers and study staff that emphasizes the importance of diversity in clinical trials.

Marc Yale, Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid Advocate

Marc shares his experience living with Pemphigoid and his passion for patient advocacy.

Donald MacIntosh, Alzheimer’s Advocate

After a 25-year career as a lawyer, Donald was shocked when he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.

Madhura Balasubramaniam, Crohn’s Disease Advocate

Madhura shares her unique perspective as an Indian woman living with IBD- a condition that faces stigma in the South Asian community.

No “Kidding”: Using Health Literacy to Communicate Clearly About Pediatric Trials

Using Health Literacy to Communicate Clearly About Pediatric Trials

The Couple That’s Empowering Communities of Color to Participate in Parkinson’s Disease Clinical Trials

Discover the Parkinson’s disease diagnosis that spurred an empowering journey Denise is still on today.

Jenn McNary, Three Sons & Three Rare Diseases

Jenn shares her experience as a mother to three children who have rare diseases with serious physical impacts.

Videos in Health Literacy

Addressing the effectiveness of videos in clinical research education

Dr. Tracy Dixon-Salazar, Lennox Gastaut Syndrome Advocate & Caregiver

Tracy shares her experience as a caregiver for her daughter Savannah who lives with LGS, a developmental brain disorder.

Health Literacy: Making Content Clear, Engaging, and Appropriate for Patients and the Public

What is healthy literacy and what is CISCRP's Health Literacy team doing?

Angie Volk, MS Advocate

Angie shares her experience living with Multiple Sclerosis and her passion for patient advocacy.

Improving Access to & Experiences of Transgender & Non-Binary Patients in Clinical Research

Improving Access to & Experiences of Transgender & Non-Binary Patients in Clinical Research

Working Towards a More Inclusive Environment: Transgender & Non-Binary Participants in Clinical Research

Learn insights on significant barriers that trans and non-binary participants face and how to create more diverse and inclusive clinical trials.

Melanie and Aaron Havert, Hemophilia Patient Advocate & Caregiver

Melanie and Aaron share their journey navigating Hemophilia A for Aaron and their daughter, Eleanii.

Richie Khan, Wolfram-Like Syndrome Patient Advocate

Richie hopes to bring awareness and education about his rare diagnosis to the research community.

Reverend Donna Matlach, Eosinphilic Asthma Clinical Trial Participant

Donna's journey with severe eosinophilic asthma led her to life-saving treatments and clinical trial advocacy.

Phyllis Kaplan, Type 1 Diabetes Clinical Trial Participant

Phyllis shares her story as a long-term advocate and and Type 1 Diabetes patient.

Desiree DeLuca-Johnson, Breast Cancer Clinical Trial Participant

Desiree shares her experience finding a clinical trial after her breast cancer diagnosis.

Melvin Mann, Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) Patient Advocate

Medical Hero Story: Melvin Mann & Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML)

Tina Aswani Omprakash, Crohn’s Disease Clinical Trial Participant

Tina’s path to becoming a health and disability advocate began with her own battle against Crohn’s disease.

TJ Sharpe, Melanoma Patient Advocate

When melanoma unexpectedly returned after a successful surgery twelve years prior, T.J. Sharpe was both a husband and a father.

Jackie Zimmerman, MS Patient Advocate

Diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS at just 21, Jackie turned her personal journey into a mission to support others.

Jillian McNulty, Cystic Fibrosis Advocate

Medical Hero Story: Jillian McNulty, Cystic Fibrosis Advocate

Shauna Whisenton, Sickle Cell Disease Advocate

Shauna shares her experience battling SCD and how advocacy has become a part of her everyday life.

Rachel Petties, Congenital Generalized Lipodystrophy Caregiver & Advocate

Rachel Petties, a mother of five, refuses to let her daughter’s rare genetic disorder define the lives of their family.

Remembering Rachel Minnick, Clinical Trial Advocate

Rachel's family and colleagues share the lasting impact she left as a mother, clinical trial participant, and patient advocate.

Shanelle Gabriel, Lupus Clinical Trial Participant & Advocate

Shanelle shares her experience living with lupus and promoting awareness and education in her community.

Juana Espino, Motherhood & Cervical Cancer

As a new mother, Juana was diagnosed with cervical cancer and made the decision to join a clinical trial for treatment.

Leah Crocker, Lupus Patient Advocate

Leah shares her medical journey to being diagnosed with lupus and how clinical research has played a positive role in her treatment.

Sandy Morris, ALS Advocate

Medical Hero Story: Sandy Morris, ALS Advocate

Katie Klatt, Battling COVID-19

After working on the front lines during the pandemic, Katie shares her experience as a both a nurse and patient herself.

Gail Graham, HIV Patient Advocate

Gail shares her experience with HIV and how clinical research, patient advocacy, and the support of her community made an impact.

Melinda Bachini, Cholangiocarcinoma Clinical Trial Participant

After being diagnosed with Cholangiocarcinoma, Melinda shares how clinical trials gave her hope.

Lee Giller, Breast Cancer Clinical Trial Participant

Medical Hero Story: Lee Giller & BRCA1

Kaamilah Gilyard, Lupus Advocate & Clinical Trial Participant

A long-time lupus patient and advocate, Kaamilah is passionate about advocacy and spreading awareness in her community.

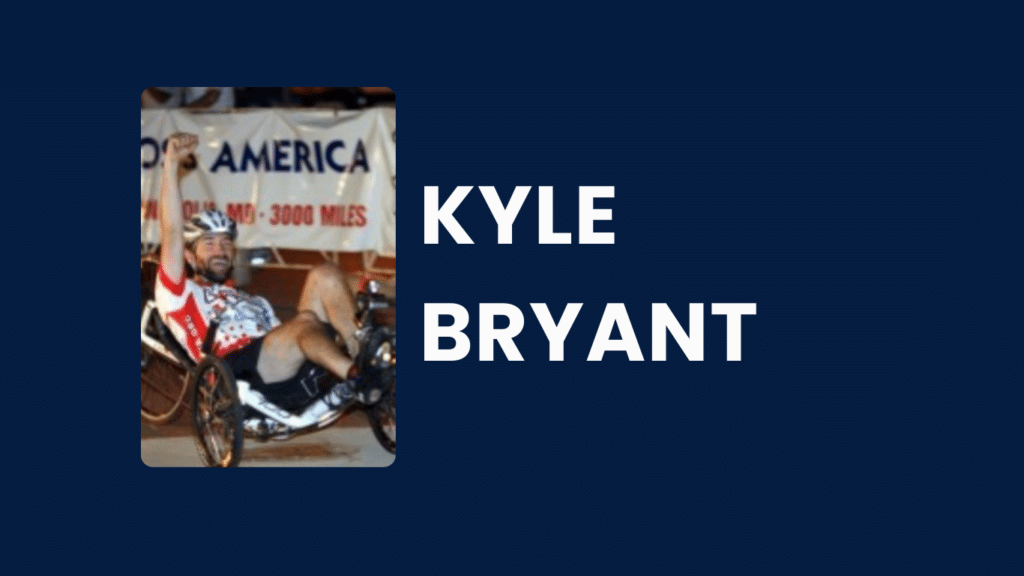

Kyle Bryant, Friedreich’s Ataxia Clinical Trial Participant

Kyle shares his experience of being diagnosed with Friedreich's Ataxia at age 17 and how cycling has played a part in his treatment and advocacy work.

Jonathan Sari, MS Clinical Trial Participant

Jonathan participates in clinical trials for his progressive MS, with the hope that a new treatment will save his life.

Luanne Bonanno, Diabetes Clinical Trial Participant

When LuAnne’s oldest daughter was diagnosed with gestational diabetes, LuAnne decided it was time to take action by participating in a trial.

Jameisha Brown, Burkitt’s Lymphoma Clinical Trial Participant

Jameisha shares her story battling cancer as child and how clinical research participation changed her life.

Pat Erickson, Parkinson’s Disease Advocate

When Pat Erickson, 57, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease 12 years ago, she refused to let it define her.